Uncovering Royal Perspectives on Slavery, Empire, and the Rights of Colonial Subjects

By Brooke Newman

Dr. Newman is Associate Professor of History and Associate Director of the Humanities Research Center at Virginia Commonwealth University. She was awarded an Omohundro Institute Georgian Papers Programme Fellowship in 2017.

In 2017 I spent a month in the Royal Archives tracing how the Georgian monarchs responded to contemporary debates over the rights and duties of British colonial subjects and the slave trade during the age of Atlantic revolutions.

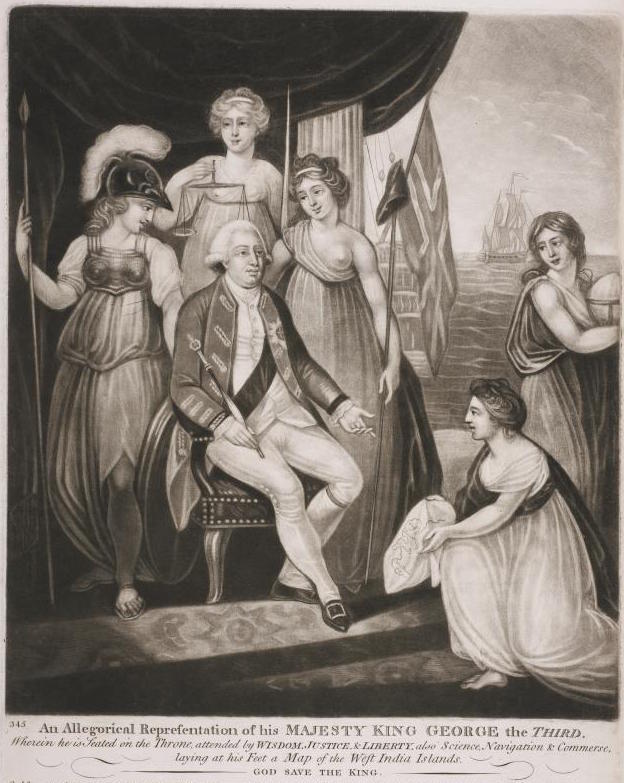

An Allegorical Representation of King George III

This research formed the backbone of a larger book-length project chronicling the evolving policies and attitudes of the British Crown and prominent members of the royal family toward imperial rule, slave trading, and colonial slavery between 1660 and 1860.

While working in the Round Tower, I concentrated the bulk of my attention on the correspondence and notes of George III, whose lengthy reign, from 1760 to 1820, saw pivotal transformations in the British Atlantic empire. Over the course of George III’s reign, Britain acquired new imperial territories and a diverse array of subjects as part of the Treaty of Paris concluding the Seven Years’ War in 1763, lost the North American colonies following the American War of Independence in 1783, oversaw the establishment of the Sierra Leone colony in West Africa in 1787, and abolished the British slave trade in 1807. Focusing on evolving monarchial responses to these events offers crucial insight into the nature and limitations of royal power in the Georgian era and the extent to which political, diplomatic, and imperial developments overlapped with public sentiment to influence Crown policy.

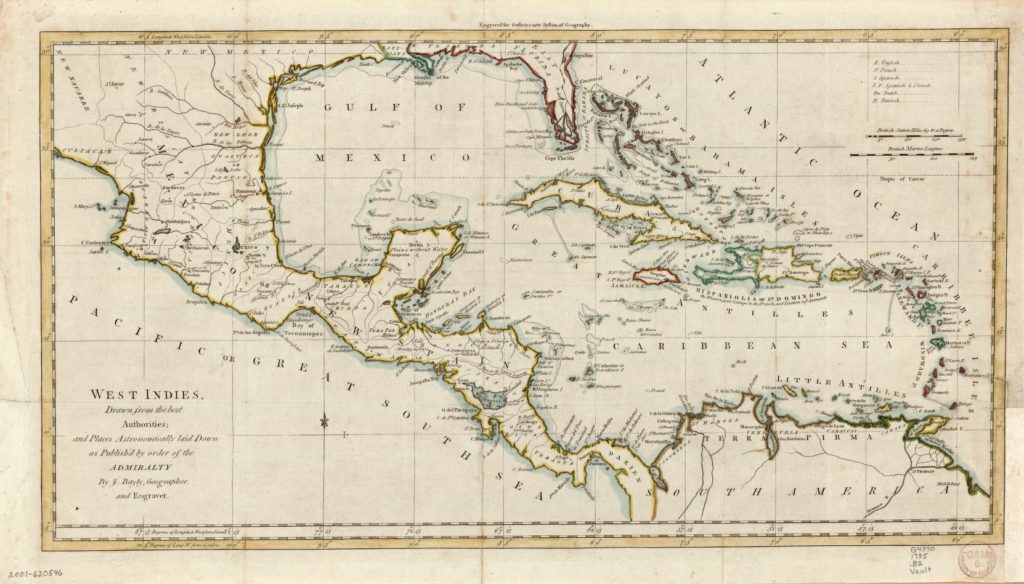

Map of the West Indies, 1785

The Calendar of George III captures the unfolding of the American War of Independence from the king’s perspective. The conflict with the American colonists, and repeated Parliamentary calls to negotiate with the rebels, prompted George III to reflect upon the imperial constitution and the bond of allegiance between monarch and subject. On May 31, 1777, for example, George III wrote to Prime Minister Lord North in response to Lord Chatham’s motion in the House of Lords for an address to the king asking him to cease hostilities in America. The king railed against Chatham’s motion to treat with the rebels, “for no one that reads it, if unacquainted with the conduct of the Mother Country and its Colonies, must [but] suppose the Americans poor mild persons who after unheard of and repeated grievances had no choice but Slavery or the Sword, whilst the truth is, that the two [sic] great lenity of this Country encreased their pride and encouraged them to rebel”[1]. As George III saw it, attempting to compromise with the rebels would signal British weakness and further encourage colonists throughout Britain’s overseas territories to challenge the authority of the Mother Country.

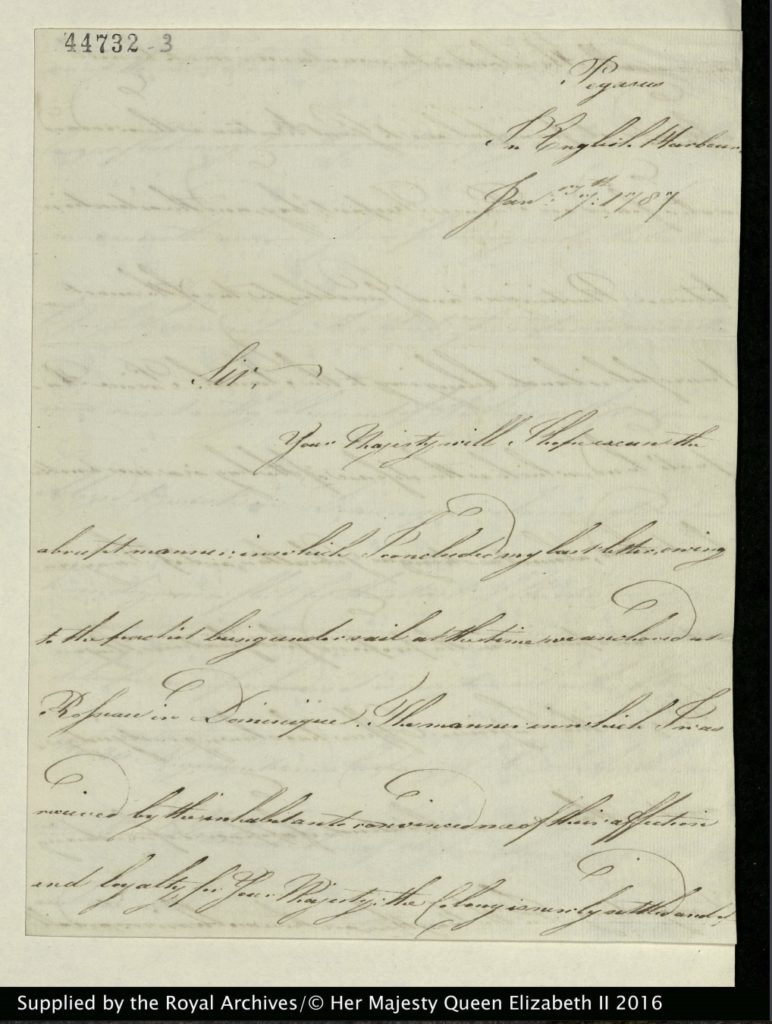

Letter from Prince William to George III, written aboard HMS Pegasus in the English Harbour, January 7, 1787

Although Britain fought to retain control of the American colonies, the Calendar of George III underscores the economic and strategic importance of the British Caribbean islands throughout the American War of Independence. Defending Britain’s sugar-producing Caribbean colonies, which generated revenue vital to national security, took precedence over reclaiming the rebel territories. “Our Islands must be defended even at the risk of an Invasion of this Island,” George III stressed in a letter to Lord Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, dated September 13, 1779; “if we lose our Sugar Islands it will be impossible to raise Money to continue the War and then no Peace can be obtained but such as one as He that gave one to Europe in 1763 can never subscribe to” [2]. The Caribbean slave colonies, particularly Jamaica, powered the Atlantic trading system and served as the economic hub of the British Atlantic empire. Consequently, in the face of a Franco-Spanish-American alliance, the British leadership concentrated on defending territories in the Caribbean and strategizing to act decisively if the opportunity arose to capture the most valuable sugar-producing island in the region: French Saint-Domingue. “Troops must be sent sufficient to secure Jamaica and Barbados, the Capital Islands belonging to this Island,” George III wrote to Lord Sandwich. Indeed, “we must run any risks rather than not Secure them if in addition to this it can be found practicable to undertake any attack on St. Domingue it would be highly desirable [3].” After the American colonies declared independence from Britain in 1783, the Caribbean remained a region of vital significance to the Crown.

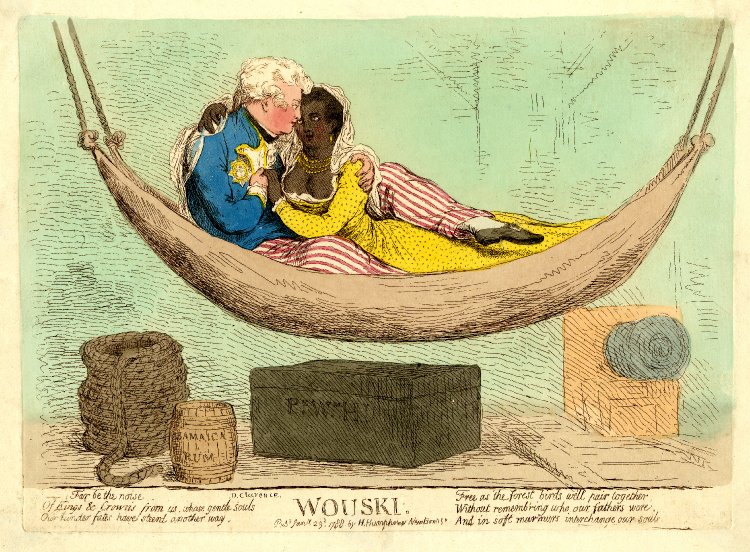

But, beginning in the late 1780s, three major events—specifically the rise of the British abolition movement, the French Revolution, and the Haitian Revolution—combined to transform the British Atlantic empire and the central place of slaveholding Caribbean colonists within it. The surviving papers of George III’s third son, Prince William, Duke of Clarence (later William IV), who was the only member of the royal family to step foot in North America and the Caribbean while serving in the Royal Navy, help to shed light on the Crown’s perspectives on African slave trading and slavery in an era of revolutionary upheaval. In 1787, on a visit to Dominica, recaptured from France in 1783, Prince William saw colonial slavery first hand and noted the island’s importance as a slave trading base. “The trade in slaves at this island is very great owing to our supplying the French with that valuable commodity,” he observed in a private letter to George III [4].  In metropolitan Britain, after rumors circulated that Prince William engaged in illicit relations with women of African descent while stationed in the Caribbean, the “Royal Sailor” became a target of satirical prints, such as James Gillray’s Wouski, published by Hannah Humphrey in 1788.

In metropolitan Britain, after rumors circulated that Prince William engaged in illicit relations with women of African descent while stationed in the Caribbean, the “Royal Sailor” became a target of satirical prints, such as James Gillray’s Wouski, published by Hannah Humphrey in 1788.

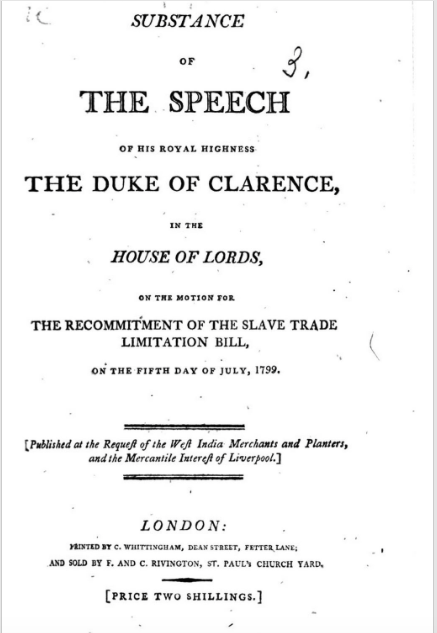

As political debates about the African slave trade escalated in the 1790s and early nineteenth century, Prince William, now the Duke of Clarence, emerged as a vocal defender of colonial slavery and a leading ally of the West India Committee in London.In 1799, in a reprinted and widely circulated pro-slavery speech delivered in the House of Lords, he referenced the long history of European involvement in the African slave trade and drew on his eyewitness knowledge of conditions in the Caribbean islands. According to the Duke of Clarence, the abolitionists had misjudged the effects of the slave trade on Africa and Africans and grossly misrepresented the treatment of enslaved men and women in the British sugar colonies. The abolitionist campaign to end the slave trade, he argued, was not only radical and misguided, like the actions of the fanatical French revolutionaries, but also deeply damaging to Britain’s national interests. Yet while the Duke of Clarence’s impassioned defense of colonial slavery helped to delay abolition, he badly misjudged the mood of the nation and, in the short term, his public image and the reputation of the royal family suffered as a result.

As political debates about the African slave trade escalated in the 1790s and early nineteenth century, Prince William, now the Duke of Clarence, emerged as a vocal defender of colonial slavery and a leading ally of the West India Committee in London.In 1799, in a reprinted and widely circulated pro-slavery speech delivered in the House of Lords, he referenced the long history of European involvement in the African slave trade and drew on his eyewitness knowledge of conditions in the Caribbean islands. According to the Duke of Clarence, the abolitionists had misjudged the effects of the slave trade on Africa and Africans and grossly misrepresented the treatment of enslaved men and women in the British sugar colonies. The abolitionist campaign to end the slave trade, he argued, was not only radical and misguided, like the actions of the fanatical French revolutionaries, but also deeply damaging to Britain’s national interests. Yet while the Duke of Clarence’s impassioned defense of colonial slavery helped to delay abolition, he badly misjudged the mood of the nation and, in the short term, his public image and the reputation of the royal family suffered as a result.

Notes

[1] GEO/MAIN/2564, His Majesty King George III to Lord North, 31 May 1777.

[2] GEO/MAIN/3518, His Majesty King George III to Lord Sandwich, 13 September 1779.

[3] GEO/MAIN/3520, His Majesty King George III to Lord Sandwich, 13 September 1779.

[4] GEO/MAIN/44732-44735, Prince William to His Majesty King George III, written aboard HMS Pegasus in the English Harbour, 7 January 1787.

Image Credits

Letter from Prince William to George III, written aboard HMS Pegasus in the English Harbour. Image provided courtesy of the Royal Archives, ref. GEO/MAIN 44732.

“Map of the West Indies,” by J. Bayly. London, 1785. Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“An Allegorical Representation of his Majesty King George the Third.” Mezzotint. Published by Laurie and Whittle, London, 1794. Image provided courtesy of the British Museum.

“Wouski,” by James Gillray. Hand-coloured etching. Published by Hannah Humphrey, New Bond St., January 23, 1788. Image provided courtesy of the British Museum.

Substance of the Speech of His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence, in the House of Lords, on the Motion for the Recommitment of the Slave Trade Limitation Bill, on the Fifth Day of July, 1799. London, 1799.

[…] Edward would use his name to nourish a near infinite spring of credit that quenched his thirst in both hemispheres of his father’s Empire. In the process, Edward demonstrated with great clarity the pathological relationship to wealth […]