LESSONS FROM THE AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR: SIR HENRY CLINTON’S ANALYSIS OF THE ALLIED INVASION OF FRANCE, 1792

By Dr Michael Rowe, Reader in European History, King’s College London

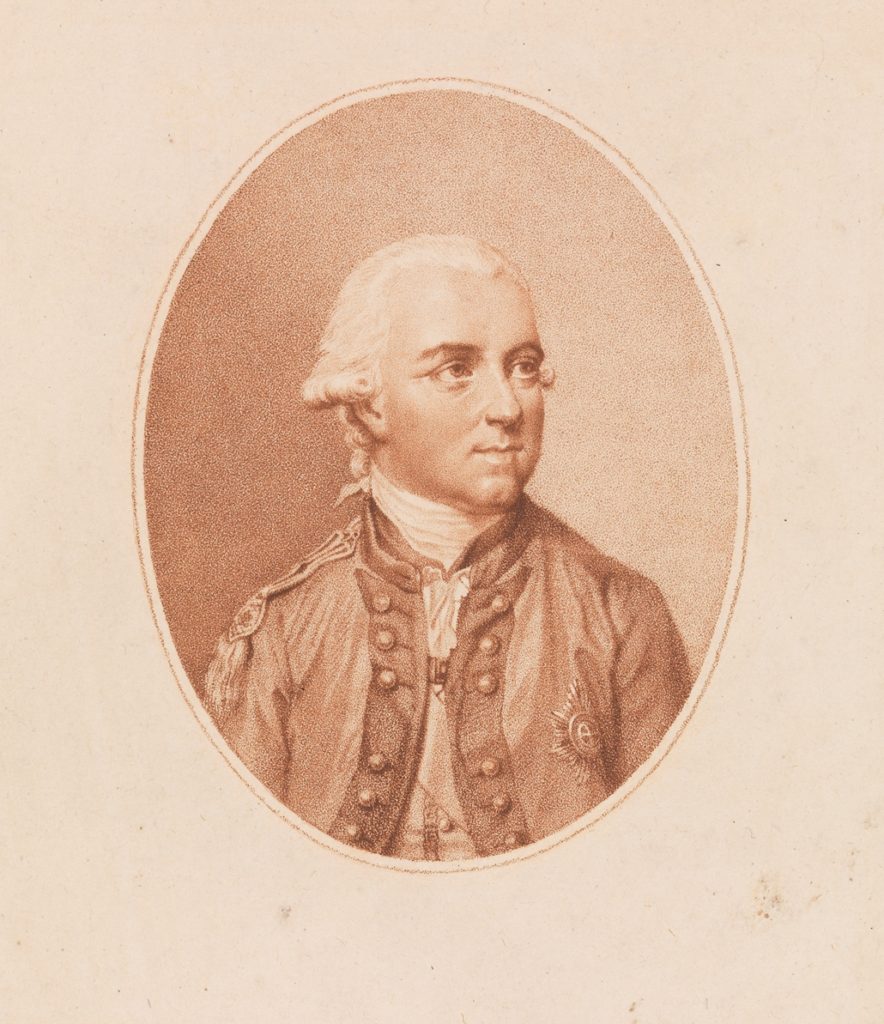

Sir Henry Clinton (1730–1795) by Francesco Bartolozzi after John Smart, published 1780: Collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

On 20 September 1792, a French army some 32,000 strong defeated a slightly larger force of predominantly Prussian troops near the town of Valmy in north-eastern France. The battle is one of the most important in history. It was by no means the largest or bloodiest of the period, but French victory ensured the survival of the Revolution. Two days later, on 22 September, politicians in Paris proclaimed the Republic. Over the coming years, French armies went on to conquer most of Europe. Much therefore flowed from Valmy and Britain, though still neutral at this stage, looked on with interest.

Three letters (GEO/MAIN/38742-38743, 38751-38752 and 38760-38761) preserved in the Georgian Papers give one British assessment of the opening phase of the French Revolutionary Wars. Written between 29 September and 27 October 1792, and addressed to George, Prince of Wales, they contain an analysis of Allied military prospects. What makes them interesting is the identity of the author, Sir Henry Clinton. Clinton is best known as Commander-in-Chief of British military forces in America from 1778 to 1782. Defeat there tarnished his reputation as military commander, though recent scholarship, including notably by Andrew O’Shaughnessy, portrays him as a scapegoat for the loss of America. Despite his shortcomings, Clinton was one of the best informed and experienced military practitioners of his day. His career as a professional soldier spanned half a century, and involved active service in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48), the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) and the American Revolutionary War (1775-83). The geographical scope of his experience included participation at a high level of command in Germany and North America, and as a military observer in the Balkans during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-74. Clinton served under some of the most respected military commanders of the age. In the Seven Years’ War, he fought in the Anglo-German army commanded by Ferdinand of Brunswick-Lüneburg that successfully defended Hanover against the French. It was in this campaign that Clinton met Ferdinand’s nephew, Charles William Ferdinand, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick. Charles William Ferdinand commanded the advanced corps of the Anglo-German army, and Clinton became his aide-de-camp and formed an acquaintanceship with him that would endure for the rest of his life.

Charles William Ferdinand’s reputation as a formidable commander was made in these years, and he became a popular figure in Britain. In 1764, he married Princess Augusta, King George III’s eldest sister, thereby solidifying the dynastic bond between Britain and northern Germany. Upon the death of his father, he became Duke of Brunswick, under which title he is generally referred to in the historical literature. In many ways he was an archetypical exponent of enlightened absolutism as then practised in German-speaking Europe. It was his reputation as Europe’s foremost military commander, however, upon which his fame rested. This reputation was enhanced in 1787 when he was made a field marshal of the Prussian army, and in that capacity directed a highly effective, swift and comparatively bloodless invasion of the Netherlands. This intervention crushed the so-called ‘Patriot’ faction, which sought to regenerate the Netherlands along more democratic and republican lines. The Patriots were in part inspired by the American Revolution, and enjoyed French diplomatic support. Opposed to them were the ‘Orangists’, who favoured a more monarchical system under the Stadtholder, Prince William V of Orange. Given his experience, the Duke of Brunswick was the obvious choice to lead the allied Prussian and Austrian forces in their invasion of France in summer 1792. Clinton visited the duke on the eve of the invasion. In August 1792, he travelled to Spa, in present-day Belgium, from where he received an invitation from the duke, who had established his headquarters nearby. According to Clinton’s biographer, William B. Willcox, Clinton viewed the conflict in global terms. He even entertained the hope that the coming conflagration between France and its enemies might extend to the Western Hemisphere, and would thereby provide an opportunity to reverse the outcome of the American Revolutionary War. Upon his return to Britain from Spa, Clinton met the Prince of Wales who asked him to put his assessment of the coming invasion of France into writing. This he did in the three letters recently made available online by the Georgian Papers Programme.

The first of the three (GEO/MAIN/38742-38743) is dated 29 September 1792. This is nine days after the Duke of Brunswick’s defeat at Valmy. From the contents of the letter, it is clear that accurate reports of the outcome of the battle had not yet reached Clinton. This is hardly surprising, given that London newspapers at this point were reporting the capitulation of French forces rather than their victory. The full extent of the French triumph had at this point not even reached Paris, which was closer to Valmy. Instead, Clinton’s letter focuses on the likely surrender of key French positions by disaffected commanders. In particular, it mentions the fortified city of Thionville, under the command of Georges Félix de Wimpffen. Clinton suspected that Wimpffen wished to defect to the allied camp. However, pointing to his own experience with Benedict Arnold, who in the American Revolutionary War had plotted to surrender West Point to British forces, Clinton stressed the importance of going through the pretence of a siege to mask the subterfuge. Clinton recognised that elements within the Duke of Brunswick’s army were all too optimistic in predicting defections, an optimism encouraged by the flight of the Marquis de La Fayette on 19 August. This optimism — or more accurately, wishful thinking — was especially prevalent among those French émigrés who, having left France after the outbreak of the the Revolution, formed a contingent within the Duke of Brunswick’s force. Clinton then correctly assessed the probability of an engagement between the French and Coalition forces on 20 September, but then incorrectly assumed a victory against the French along the lines of earlier battles: the letter mentions engagements near Mons and Tournai, references respectively to the battles of Quiévrain and Marquain. Another victory, so Clinton thought, would allow Brunswick to advance towards Paris via Châlons.

Clinton then stood back from further speculation about military deployments, which were presented as fairly straightforward, and took in the wider political picture, which was more confused. The problem as Clinton saw it was the domination of Paris by radicals concentrated especially in Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marcel. Should they retain the upper hand, then for Clinton there was a real danger that the Duke of Brunswick’s advance would provoke the murder of Louis XVI and anarchy. However, if the moderate faction was to win control and surrender Paris, Clinton feared the war would not end either. Instead, there would be the prospect of having to defeat twenty million ‘enthusiasts’, a task so great that it would require the intervention of all France’s neighbours including Britain. Clinton ended with a postscript, apparently added after reading newly published letters of the French military commanders, Charles François Dumouriez and François Christophe Kellermann, reporting success. However, Clinton concluded by discounting these as forgeries, published, he speculated, out of the need on the French side to present a victory in order to solidify public support for the new constitution.

The second letter from Clinton (GEO/MAIN/38751-38752) is undated, but was sent ‘some weeks’ after the first, and hence dates from about the third week of October. In this letter Clinton acknowledged that recent events had proved how ‘ill founded’ his previous ‘conjectures’ had been. The letter refers to the ‘strange mystery’ and ‘most unaccountable mystery’ that had hung over recent military events, and notably the actions of the King of Prussia, Frederick William II. In particular, Clinton expressed some doubts as to whether the Prussian army’s position was really so weak as to justify either a rumoured truce with the French or to explain its retreat. Clinton also noted insinuations that Frederick William had been trying to ‘debauch’ Dumouriez, though these were ‘probably without the least foundation’. The whole impression conveyed by the letter is that neither the Prussian nor French forces were any longer seriously engaged against each other, and also of a possible imminent ‘change of system in Prussian politics’.

The third and final letter (GEO/MAIN/38760-38761) is dated 27 October. Here, Clinton describes the whole subject of the operation of the allied armies as having ‘become a very disagreeable one’. Clinton goes on to explain that he has now modified his earlier opinion about the reason for the Prussian army’s apparently precipitous retreat in the days after Valmy. His initial opinion had been that the King of Prussia had believed himself to have been deceived by the two princes of the blood (Louis XVI’s brothers, Provence and Artois, who were leaders of the emigration) about the ease with which revolutionary France might be defeated. Developments in France, including the suspension of Louis XVI and the new constitution, might have given Frederick William an excuse to withdraw claiming the principle of non-interference in domestic politics. Clinton did not dismiss this version entirely – ‘if there is any foundation for any of these opinions, time will show it’ – but went on to re-evaluate other grounds for the Prussian retreat. Clinton treats these essentially military reasons as highly credible. In particular, he referred to the ‘adverse elements’ that had ‘reduced almost to incapacity’ a ‘fine army’. This was a reference to the dysentery that did indeed afflict the Prussian army at the time of Valmy. Clinton reminded the Prince of Wales that illness, from his own experience, is an ‘enemy … most to be dreaded tho[ugh] seldom thought of in military calculations’. Thanks to the manoeuvering of the French forces under Dumouriez, and the retreat of an allied Austrian force under the Duke of Teschen which was besieging Lille, the Prussian army needed to retreat in order to secure its line of communications. The ‘incessant rain and bad weather, badness of roads and tardiness of supply’, but above all, the number of sick, obliged it to retreat to the Meuse. Clinton promised to forward to the Prince of Wales a copy of the Gazette de Bonn which reported ‘treachery’, ‘tardiness’ or ‘timidity’ on the part of the Austrians. Clinton’s final letter also contains a transcription from a note he had received the previous night from the Duc de Coigny, a leading figure in the French emigration, who was passing through Harwich on his way back to the allied forces. The note was dismissive of the rumours surrounding events and instead stated that it had become impossible for the Duke of Brunswick to advance further because of the bad roads (which made it dangerous to move too far ahead of supplies), and also the large number of sick caused by the bad weather. These factors made it logical to postpone campaigning until the next season. Clinton concluded by expressing doubts as to Prussia’s intention of continuing with the campaign by noting its recent evacuation of Longwy, a key strategic town on the northwestern border.

Collectively, Clinton’s letters convey the ‘fog of war’, which made it hard even for a military specialist to reconstruct the course of events. This ‘fog’ was thickened by the complicated politics of the opening stages of the French Revolutionary Wars. Both sides in the conflict were internally divided. The Austrians and Prussians suspected each other of underhand dealings, and both mistrusted the émigrés. Clinton, of course, with his American experience, would have been especially sceptical about émigré assurances of vast numbers of royalists ready to rise up upon the appearance of external military forces. The French were equally divided, with some moderates like Clinton’s old opponent, the Marquis de La Fayette, defecting. Finally, the letters are also illustrative of the eighteenth-century trans-national network of military practitioners. Military experts engaged with one another irrespective of nationality or dynastic loyalty. Their network operated in the professional rather than political dimension, and facilitated the transfer of knowledge between the successive global wars that characterized the eighteenth century and reshaped the Atlantic World.

Further reading

T. C. W. Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars 1787-1802 (London: Arnold, 1996).

Charles J. Esdaile, The Wars of the French Revolution: 1792-1801 (London: Routledge, 2018).

Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men who Lost America: British Command during the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire (London: Oneworld, 2013).

Paul W Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics 1763-1848 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994).

William Bradford Willcox, Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964).

Michael Rowe is Reader in European History at King’s College London, which he joined as a Lecturer in 2004 after teaching at Queen’s University Belfast. Prior to that he held a Prize Research Fellowship at Nuffield College Oxford after completing his PhD at Cambridge University and his undergraduate studies at King’s College London. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. He has published widely on the era of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, and the decades immediately before and after. He is especially interested in the growth of the state in Europe and the rise of nationalism. More recently, this has developed into a focus on the role of religion in the politics of various European states in the period spanning the eighteenth-century Enlightenment to the emergence of nation states later in the nineteenth century. His most recent book is War, Demobilization and Memory: The Legacy of War in the Era of Atlantic Revolutions, coedited with Karen Hagermann and Alan Forrest (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

Michael Rowe is Reader in European History at King’s College London, which he joined as a Lecturer in 2004 after teaching at Queen’s University Belfast. Prior to that he held a Prize Research Fellowship at Nuffield College Oxford after completing his PhD at Cambridge University and his undergraduate studies at King’s College London. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. He has published widely on the era of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, and the decades immediately before and after. He is especially interested in the growth of the state in Europe and the rise of nationalism. More recently, this has developed into a focus on the role of religion in the politics of various European states in the period spanning the eighteenth-century Enlightenment to the emergence of nation states later in the nineteenth century. His most recent book is War, Demobilization and Memory: The Legacy of War in the Era of Atlantic Revolutions, coedited with Karen Hagermann and Alan Forrest (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).